The business model of college football, long a financial boon to universities, is breaking down. This is the last in a weeklong look at the pressures of rising costs, falling revenue, and what, if anything, universities can do about it. Read the rest of the series here.

The University of Alabama is favored to beat Clemson in the college football championship tonight and with good reason. The Crimson Tide played a harder schedule than the Tigers, gave up fewer points, and went undefeated. At the end of the season, Alabama finished first in all six College Football Playoff polls; in the Associated Press ranking, the team got all 61 first-place votes.

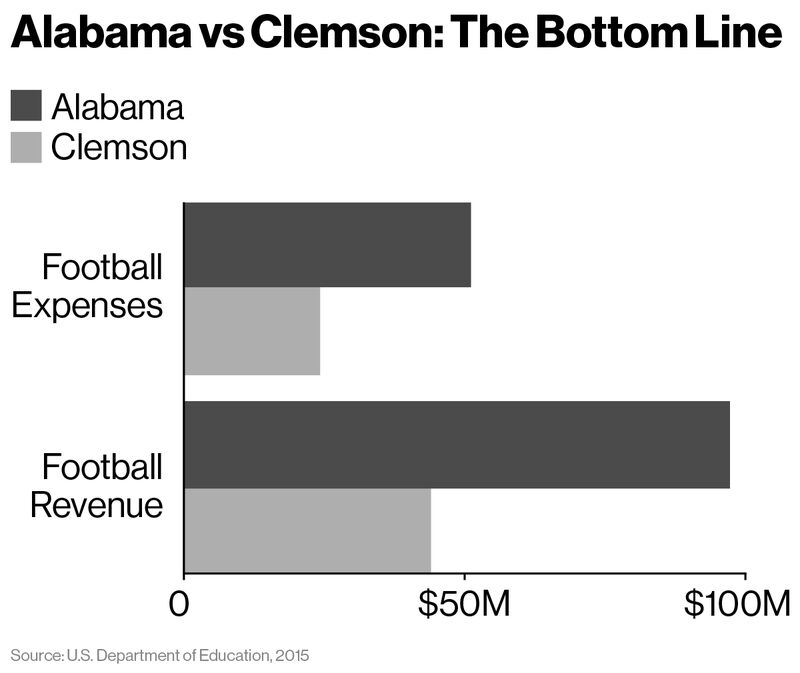

Off the field, the contest is even more lopsided. Clemson spent $24 million on football in 2015, more than 75 percent of top-tier football schools—and still less than half of the $51 million football budget at Alabama.

The Crimson Tide also earns more: Alabama’s football program brings in $97 million, more than twice what Clemson’s does—in fact, more than the South Carolina school’s entire athletics budget.

The financial chasm that separates Clemson from Alabama—the biggest college football dynasty since 40s-era Notre Dame—is a potent illustration of the disparity across college football. Alabama and about a dozen others are college football’s ultimate “haves,” supported by a system that allows the richest schools to make their own rules.

These schools are insulated from the pressures football is starting to place on many schools around the country, where the sport requires subsidies from the other side of campus to make up for falling attendance and rising costs. “They’re almost completely immune,” said Russell Wright, the managing director of Collegiate Consulting in Atlanta, which has studied the finances of college athletic departments at every level.

Powered by football, schools in the Atlantic Coast, Big Ten, Southeastern, Big 12, and Pac-12 conferences (the Power Five) spent an average of $90 million on athletics in 2015. The rest of the schools in college football’s top division, excluding Army, Navy, and Air Force, spent, on average, one-third as much.

New TV deals will widen that gap, as networks are willing to pay more for the best schools and less for the rest. The Big Ten is about to begin a media deal worth $440 million per year, a threefold increase over its last contract. In contrast, Conference USA, home to such programs as Marshall, Old Dominion, and Louisiana Tech, agreed to a television contract worth $2.8 million per year, according to the Virginian-Pilot, a 72 percent decrease from its last deal.

Membership in a top conference does not, by itself, turn a school into a juggernaut. Plenty of schools in Power Five conferences spend a more modest amount on football. Mississippi State spent $17 million in 2015. Oregon State spent $15 million, less than some schools from less powerful conferences.

Schools with annual athletics budgets north of $120 million, including Oklahoma, Florida, Michigan, and LSU, are enhanced by a slew of business lines that aren’t as lucrative for smaller programs. At Ohio State, for example, the athletic department is in the middle of a 10-year, $128 million agreement with IMG College, a media rights middleman. A 15-year, $252 million apparel deal with Nike Inc. begins in 2018. Last year, the Buckeyes earned roughly $15 million in annual licensing royalties.

“We are much more diversified in our revenue portfolio,” said athletic director Gene Smith. Those deals “all have upside that other schools do not have.”

In other words, when the Nike deal kicks in, Ohio State could make $45 million on top of ticket sales, alumni donations, and its share of Big Ten television revenue. That extra money alone is more than the entire athletic department budgets at 53 top-tier football schools.

In addition to covering the department’s costs and athlete scholarships, Smith and the Buckeyes contribute to the university’s overall budget. Ohio State athletics transferred $9 million to the school in 2014, according to data that schools submit annually to the National Collegiate Athletic Association. It is one of seven programs that give back more than $4 million.

Recently the structure of college football changed to confer an even bigger advantage on the most powerful conferences. Starting in 2015, the NCAA granted what’s known as autonomy to the Power Five, allowing them to make their own rules in such areas as financial aid and insurance. Other schools were welcome to try to keep up.

The Power Five quickly used its new freedom to provide additional money to athletes, an added $2,000 to $6,000 a year intended to make up for shortfalls in the traditional athletic scholarship. It also immediately threatened to give the schools an edge in recruiting, which has a domino effect: Better players lead to better teams, which leads to more money, which in turn enables the schools to spend more on recruiting.

So far other schools and leagues are trying to match the increased spending, even though their revenue streams are rarely as robust. Most, for example, are offering the same scholarship stipends.p.c:https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2017-01-09/alabama-trounces-clemson-and-everybody-else-in-the-college-football-money-game

“It forces most others to follow suit, whether they’re in the same boat financially or not,” said Todd Stansbury, the athletic director at Georgia Tech. The school has a $64 million athletic budget and still feels the strain. “That’s definitely a concern, because I’ve never been at a place that was that flush with cash.”

A money-is-no-object approach to big-time football is often justified by the exposure a university gets from its team. Every bowl game is, essentially, a three-hour ad on national television. Every championship attracts more student applicants. At Alabama, enrollment has nearly doubled, to 37,000, in the past 13 years, a period that includes the hiring of coach Nick Saban, four national football championships, and a $2 billion investment in campus infrastructure.

It’s that kind of payoff that keeps other schools in the hunt, even as the revenue model weakens. “The dynasty programs will be the last ones to feel the shifting landscape,” said Karen Weaver, a sports management professor at Drexel. “That’s the problem that we have. We can’t keep looking to become the next Ohio State.”

To be fair, even college football’s dynasties worry about the future. The NCAA is facing legal challenges—specifically, antitrust lawsuits that focus on giving athletes a larger share of sports revenues—that threaten every school. And no one knows how long the media money will keep flowing. “If things stay the way they are,” says Alabama athletic director Bill Battle, “I’m very comfortable.”

Just in case they don’t, Alabama athletics has set aside a reserve fund of about $180 million, enough to cover the costs of the entire athletic department at most top-tier football schools for three years.

No comments:

Post a Comment